What you find fun in a game depends a lot on your personality and experience. But can the elements of a game that players enjoy be generalised or categorised? What does the science say about how to design a game that players cannot put down? Let’s have a look at two theoretical models by Richard Bartle and Nick Yee which describe player types and engaging game elements, respectively.

Why do we play games? Well, games are fun, you might say. But what exactly makes you come back for more? There are actually many different reasons for people to play, many different things they are looking for in a game. Most likely, they have a favourite genre — but which game elements that constitute that genre are the most important ones? Which ones catch the player’s attention, which ones sustain their engagement — and why?

Player motivation — to play games in general or a particular one — can, of course, be analysed. Self-assessment, anecdotes and intuition aside, there is actually quite a bit of scientific literature on the topic. As you may have read in my previous article, I wrote my Master thesis about it. To be more precise, the thesis was entitled ‘Player Engagement: Langzeitmotivation durch Game Design und Marketing am Beispiel von Diablo III und Hearthstone (Long-time motivation by game design and marketing at the example of Diablo III and Hearthstone).

As a scientific basis for my analysis, I looked at two theoretical models that were similar in some regards and different in others. I am going to explain them to you and show you how you can use this knowledge to design better games, that is, games that players want to play again and again.

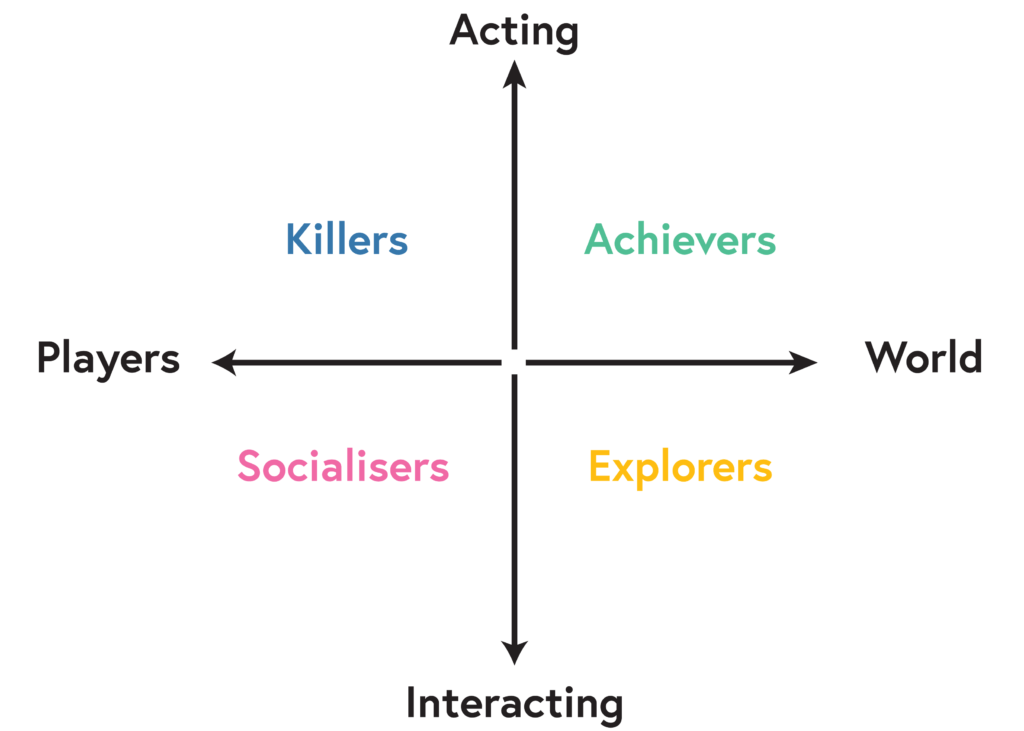

Richard Bartle: Analysis of Player Types

As in my thesis, let us start with Richard Bartle. Similar to psychometric models — for example, the OCEAN model (Openness, Conscientiousness, Extraversion, Agreeableness, Neuroticism; also called the Big Five) or the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI) —, Bartle’s model is based on the assumption that people can be sorted into categories, in this case defined by the primary motivation to play games. His taxonomy started with four player types and was focussed on massive-multiplayer games. The player types the model suggested were:

- Killers: PvP-oriented players who seek competition. Think of e-sports.

- Achievers: Players who want to achieve something the game content itself provides, for example gaining levels, finding items or completing side quests. Think of quest journals, item catalogues and beastiaries.

- Socializers: Players who treat the game more or less as a social media platform. Think of guild leaders.

- Explorers: Players who try to completely immerse themselves by exploring every corner of the game world and putting together every little piece of lore. Think of Dark Souls.

Bartle later expanded this four-type model by adding another binary dimension (implicit/explicit), thus doubling the number of types to eight. If you want to learn more about the expanded types, you could simply start with this Wikipedia article.

The problem with a player-type approach, however, is similar to what the MBTI is criticised for: Players must be sorted into a single category even if their motivation is multi-facetted. In the MBTI, if a person answers the questionaire in a way that gives them a 51% introversion rating, the MBTI assigns them that label in a boolean fashion (that is, with no information about the degree of the introversion), so the test may easily have the opposite result when giving slightly different answers a day later. In Bartle’s player-type assessment, If a player is motivated by raids — achievements as a team —, they are either achievers or socialisers; they cannot be both. Thus, half of the player’s motivation is practically discarded for no reason other than simplicity.

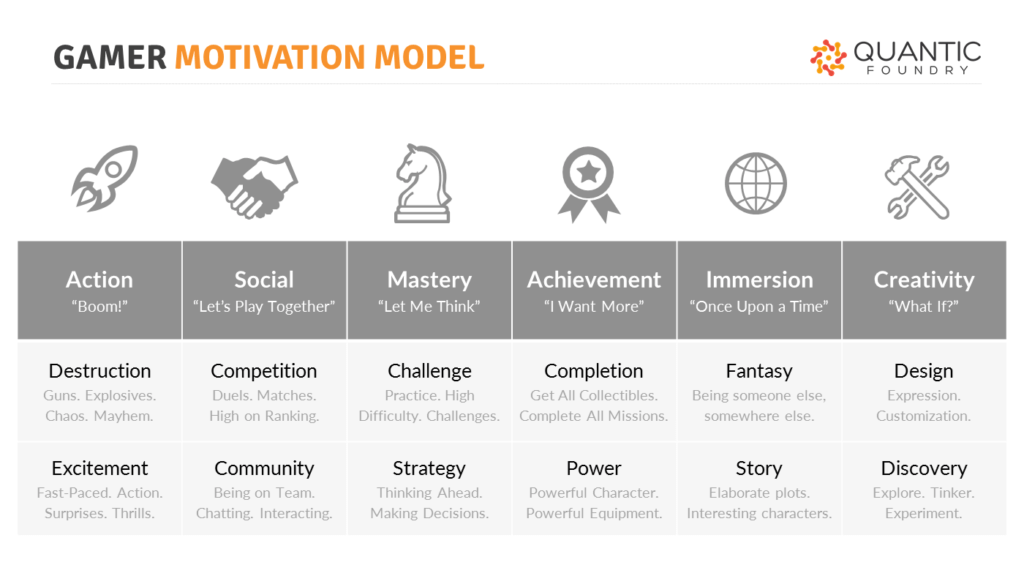

Nick Yee: Analysis of Player Engagement through Game Elements

The second model of player motivation that I included in my thesis was formulated by Nick Yee — who may be known to some of you, for example from this GDC talk or this one. In contrast to Bartle’s taxonomy, Yee’s model is not a player-centric, but a game-centric one. After careful analysis of survey data, he came up with a model that consists of 12 elements a motivating game can be built around. Games may vary in the degree each element is present — and some may be missing entirely, especially in older games with limited content —, but the theory suggests that a game which successfully captures and maintains a player’s interest probably contains at least one element from the following list:

- Destruction: His basically means explosions and chaos. Players attracted by this aspect of a game want to see the world burn. And things break.

- Excitement: Fast-paced, thrilling action. Racing games come to mind, but also fast characters in action games. Players drawn to such games will probably choose Sheik over Ganondorf in Smash Bros.

- Competition: PvP in various forms. This category is pretty straight-forward: Players want to compete against other players either in duels, in team-versus-team settings or asynchronously, for example by out-speedrunning them or by achieving higher scores.

- Community: This comprises guilds, chats, emotes and other features that enable player interaction in a cooperative manner.

- Challenge: Difficulty and practice. A good example are jump’n’runs like Donkey Kong Country with levels which pose a challenge in terms of fast reactions and eye-hand coordination and which tend to become easier with each attempt.

- Strategy: Planning ahead and making good decisions. As the name suggests, strategy games rely heavily on this category, but games from other genres may contain strategic elements as well. RPGs, for instance, may require you to build your character with a certain goal in order to maximise the effectiveness of their skills. In card games like Hearthstone, you want to build decks with synergetic effects between cards.

- Completion: 100%ing everything. A completionist wants to do all the side quests, find all the items and max out their characters just for the sake of ticking these boxes. They may not actually use any of the quest rewards.

- Power: Becoming invincible and one-hitting everything. Players who are motivated by a fantasy of power want to max out their characters so they can obliterate even the strongest opponents with ease.

- Fantasy: Being someone else somewhere else. Western RPGs do this very well in allowing you to create your own character as far as appearance, personality and abilities are concerned. They also tend to provide a lot of dialogue options and world-building lore.

- Story: Cool setting, awesome plot twists. This is what JRPGs do very well in contrast to Western RPGs: presenting you a predefined cast of interesting characters and a story that often goes from very basic tasks (fighting stupid-looking slimes in the forest nearby) to an epic finale (fighting a powerful god in another dimension).

- Design: Building your own stuff. For example a city in Sim City. Or stages in Super Mario Maker. Or your own house in an MMORPG.

- Discovery: Finding secrets and easter eggs hidden by the designers. Or just venturing into a new, mysterious area in an open-world game.

With a theoretical model that focusses on the games themselves rather than the players, the overlap between categories does not constitute a problem anymore. Players can be attracted by multiple game elements — even all 12 of them! —, resulting in something like a motivational profile for each player. For these profiles to be even more precise, you can view the elements as dimensions — see OCEAN model — and give each of them a rating indicating how important exactly they are to the player.

Examples from my Games

So, having studied the topic, have I actually implemented any of this knowledge in my games? I would hope so. Let us break it down by category and see what is in Game Master, Game Master Plus or LV99: Final Fortress:

- Destruction: Smashing urns just for 1 Gold? Devastating AoE spells? Check. While a JRPG is not a shoot ‘em up, you can (and should) at least place a few destructibles on the maps for those who seek to wreak havoc.

- Excitement: Well, yeah … There are actually next to no moments in my games that significantly turn up the speed — which may, however, be a good thing in a game that targets a more strategy-focussed audience. That said, one or two fast-paced segments might find its way into my next game for strategy-focussed players who also enjoy some frantic second-to-second gameplay.

- Competition: There is no multiplayer and there are no highscores. Players who like to compete would have to come up with their own challenges, for example speed-running or low-level-running the game. Still, I should at least think about ways to make my next game more competitive, and be it only asynchronously.

- Community: As single-player experiences, none of games have any community features. Engagement with other players is only possible by talking not in the game, but about it – on Facebook or Instagram for example, on the RPG Maker Web forums or on forums like RPGWatch.

- Challenge: ‘Easy-going with optional challenges’ is my design approach when it comes to difficulty. While JRPGs do not consist of stages with a learning curve, some boss encounters in GM, GMP and LV99 may actually require you to ‘read’ the enemy and memorise their skill cycles — which is arguably similar to learning the sequence of obstacles in a DKC mine cart stage. Minigames would be a way to include ‘real’ challenges in the sense of Yee’s model, but I, as a player, tend to not be very interested in minigames and thus have not felt the urge to include any in my games. Maybe it is time to try it, though.

- Strategy: Strategy in terms of building your characters for maximum efficiency is at the core of Game Master, Game Master Plus and LV99: Final Fortress. You get to choose which pieces of equipment and which skills to bring into battle, taking into account the strengths and weaknesses of characters and enemies.

- Completion: Like in any good JRPG — and, in fact, most games —, there are tons of things to complete and to collect. This category is actually pretty hard not to check when it comes to game design. In the most recent Game Master Plus patch, I made sure that there are no missable items anymore, so completionists are not forced to start over again because they have missed something minor in their catalogue.

- Power: Levelling up, finding stronger equipment, buffing characters in battle — while there is little linear equipment progression (in favour of choices between equally strong alternatives), there are many ways to raise stats, learn skills, activate abilities and gain power in my games.

- Fantasy: You can definitely feel like someone else somewhere else in my games. The role-playing aspect becomes obvious when being presented with class and dialogue choices. I will be honest, though: I, personally, love character creation in RPGs and would love to have it in my games, but in RPG Maker, it is very hard to pull off.

- Story: In Game Master and Game Master Plus, the story starts mysterious and becomes epic later on. I have no regrets as far as this aspect of my games is concerned. Nonetheless, me and my novel-loving girlfriend will try to write an even better story for the next game!

- Design: Being built in RPG Maker, there is little I can do for those of you who would like to design your own stuff. I have tried to make the equipment choices as interesting as possible, so you can at least kind of ‘design’ the characters as far as stats, skills and abilities are concerned.

- Discovery: There are lots and lots of secrets in my games! If you are observant, you will not only find hidden places, but also easter eggs and references to other games. I hope that someday, there will be a ‘perfect’ letsplay of my games like the ones HCBailly is known for, showing the optimal strategies, most efficient puzzle solutions and secrets.

As you can see, science has in fact had some impact on the design of Game Master, Game Master Plus and LV99: Final Fortress. That said, I believe that Yee’s categories are rather broad, so as a game designer, you should try to maximise the fun by designing well even *within* the categories.

For example, having items to collect for the completionists is great, but you cannot just throw a bunch of them in there and hope for the best. Take The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time as an example: Beside other things, you collect Rupees, Skulltulas and Heart Pieces (or Pieces of Heart). Rupees can be found all the time. The world is littered with them.

Skulltulas, on the other hand, are limited. There are 100 of them in total, most of them hidden, but audible, so they require the player to be observant and listen for the characteristic sound effect. Finally, there are 36 Heart Pieces which you often receive as sidequest or minigame rewards. There is some overlap, in that Heart Pieces can also be found hidden in some places — much like Skulltulas —, but for the most part, these three types of collectibles serve different purposes.

Having a concept like this for each one of your ‘elements of fun’ seems like a good idea to me. What types of destructibles do you want to include, and why? Which community features are the most effective, which ones actually redundant? Do you really need a separate monster-hunting side quest for each enemy in the game, or would a beastiary suffice, with rewards for every 10% completion? Take a step back and ask yourself what your game content is actually supposed to achieve, then design for efficiency.

Conclusion

In conclusion, simply designing the ‘game you would love to play’ may not be enough. You may be wasting your time and money on game content that ultimately does not convert casual players to ardent fans. Science helps us understand which aspects of player psychology and game design need to be taken into account in order to create the right type of interaction: the one that drives engagement effectively.

***

So, tell me: What is it that you enjoy most in a game? And what elements could you do without? Do you see major differences between yourself and most other players?

Very well worded!

Thanks! 🙂

You are a great writer!

Oh, thank you! 🙂 Doing my best.

I really like your blog.. very nice colors & theme. Did you create this website yourself or did you hire someone to do it for you? Plz answer back as I’m looking to create my own blog and would like to know where u got this from. thanks

It’s a WordPress theme. 🙂

I’m really impressed with your writing skills and also with the layout on your blog. Is this a paid theme or did you modify it yourself? Either way keep up the nice quality writing, it is rare to see a great blog like this one these days..

Thank you! 🙂 I’m using Neve as a theme.

Very good website you have here but I was wanting to know if you knew of any community forums that cover the same topics talked about in this article? I’d really like to be a part of online community where I can get advice from other knowledgeable individuals that share the same interest. If you have any suggestions, please let me know. Many thanks!

There’s https://forums.rpgmakerweb.com/ — and I’m sure if you google ‘indie game development forums’ or search Facebook groups for something along those lines, you’ll soon find what you’re looking for. 🙂

very nice publish, i definitely love this website, carry on it

you’ve a great weblog here! would you wish to make some invite posts on my blog?

Thanks! 🙂 Where can I find your blog?